|

National Geographic chief recalls Rogue Valley roots

|

Zach Urness/Daily Courier

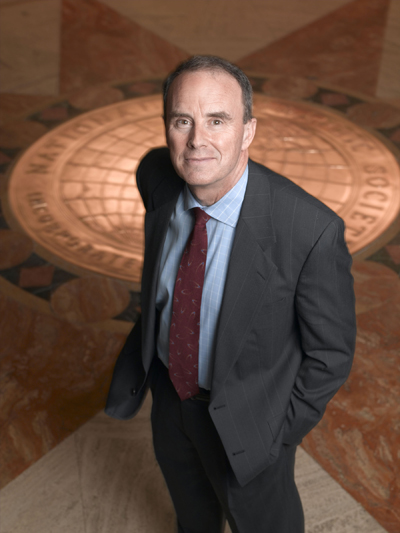

Chris Johns, who grew up in Central Point, Ore., is the editor in chief of National Geographic. |

Chris Johns, the editor in chief of National Geographic magazine, grew up in Central Point and developed his love for the outdoors in Southern Oregon. o o o oBy Zach Urness of the Daily CourierChris Johns still remembers the wanderlust he felt reading National Geographic magazines on rainy Saturday afternoons at his grandfather’s home in Grants Pass.Chris grew up in Central Point during the early 1960s, but each Saturday his family drove to Grants Pass so his father could work at a menswear store called Utz For Suits, owned by his grandfather Glenn Utz. While his dad sold neckties and cufflinks, Chris spent the afternoon in his grandfather’s house on Savage Street, reading about native tribes in Africa and the ruins of ancient civilizations in a magazine that seemed to bring the world to his fingertips. “It fed a real wanderlust in me,” Johns recalled. “My grandfather had a big bookshelf in his study, and I’d pick out National Geographics then spend a rainy winter afternoon absorbed in them.” The desire to see the world eventually took the 1969 Crater High School graduate across the globe as a photojournalist. After graduating from Oregon State University, earning a master’s degree from the University of Minnesota and winning the National Newspaper Photographer of the Year award in 1979, Johns began a freelance career that took him from Africa to Alaska. In 1985 he became a contract photographer for National Geographic, and in 1995 Johns joined the staff. Ten years later, the boy from the Rogue Valley was named editor in chief of the yellow-bordered magazine that once inspired him. Johns is the ninth editor of the magazine since its founding in 1888. National Geographic has a worldwide circulation of 35 million and is published in 33 languages. Johns’ Southern Oregon roots remain deep. He’s the grandson of a logger and millwright. His father was a social studies teacher and principal at Mae Richardson Elementary School in Central Point. Johns worked for local farmers growing up and went hunting, backpacking and fishing on the Rogue River. And though he’s best known as the first photographer to reach the magazine’s top slot, it’s becoming National Geographic’s first editor from the West that he feels best defines him. Last Friday, I caught up with Johns while he was at his offices in Washington, D.C. The conversation included his memories of the Rogue Valley, the debate on environmentalism and the day he accidentally intruded upon a pride of lions. Johns, who is married and has three children, has traveled far and achieved a great deal. Yet it’s obvious that the kid who spent rainy afternoons in his grandfathers’ study never has lost his wanderlust. ZACH URNESS: You recently wrote that as a child, you had a habit of disappearing into the woods. What were some of your favorite places to disappear in Southern Oregon and Northern California? CHRIS JOHNS: Jedediah Smith Redwoods Park was a magic place for me as a kid ... it seemed like something out of a Lewis Carroll novel. I used to lie on my back and wonder what it was like at the top of those trees. I came back when we did the cover story on the Redwoods (October 2009) and got the picture of a Redwood from the top to the bottom. I hiked with my wife and 13-year-old son. It really was great to be back. Other places I loved were Crater Lake, especially in the winter, and the Pacific Crest Trail. And it doesn't get much better than fishing for steelhead on the Rogue River. ZU: You traveled across the world as a photographer for National Geographic. What were some of the craziest moments you encountered? CJ: Once in Zimbabwe, we accidentally walked into a pride of lions, and that got pretty interesting. We'd been tracking them and made a pretty big mistake. We surprised them and they surprised us. We were charged by a couple of big males, and I remember one coming toward us, with his mane flapping and obscuring his face, and letting out a big roar that rattled my bones. We were stalked by a young female, too. We slowly backed out and it was OK. But that’s something I’ll always remember. ZU: What do you see as the mission of National Geographic? CJ: We go to tremendous lengths to deliver unbiased information about the relevant issues of our time ... stories that capture the imagination, and to inform, educate and inspire people about the world we live in. We work with extremely smart, dedicated people steeped in science and intellectual curiosity. We try to build bridges from them to our citizens by getting the facts with no agenda. We try to build cultural bridges, to report from the far corners of China, so in today’s world we understand why the Chinese make the decisions they do. We report on Islam ... that yes, there are radical elements with a frightening agenda, and we try to understand how its gotten to this point. We try to show that there are lots of reasonable, common people (within Islam) that share our values. ZU: The environment has become an increasingly political issue. Does that ever become a problem when you’re reporting on a controversial topic? CJ: Evolution and climate change are very emotional, hot-button issues. We feel that it’s really important to bring out the facts. People from both the left and right sometimes scream at each other about these issues. We don’t scream. We say, ‘Listen, this is really interesting. Let’s look at the facts.’ We have a long history of pulling people together. We're not a for-profit magazine. We don’t have to answer to stockholders, which gives us a great advantage. ZU: Do you think there will always be conflict between environmental conservationists and those who want to use the land for more logging? Is there a happy medium? CJ: I think there has to be a happy medium. We all get passionate, but we have to listen to each other. I get annoyed with people on both sides of the issue who simply close down and get angry. When my grandfather started logging in Oregon, it was a different world. I am proud of what he accomplished, but there are a lot more issues facing us today. We have huge challenges ahead of us, and yelling and screaming at each other is counter-productive. Good science will get us where we need to be. DC: Do you think growing up in the Rogue Valley helps you appreciate the complexity of an issue such as conservation vs. land use? CJ: Very much so. It all goes back to my family. My grandfather took a great deal of pride in being a logger and millwright. But he also loved the outdoors. I’ve never been in the coastal range with anybody who knew or understood the ecosystem and nature better than he did. Hunting for deer or black bear with him, as a young man, was incredibly important to me. ZU: Growing up, did you ever see yourself working at National Geographic? CJ: I went to Oregon State to study agriculture, and for a while I actually thought I wanted be an agriculture teacher. I even pulled out of school for a few months to be an agriculture teacher in Eagle Point, which I really enjoyed. That job made me enough money to buy a camera, stick it in my backpack and hit the trail for the weekend. That experience — being in the outdoors with a mission (to take photographs) — convinced me that there were other things I might like to explore in photography and journalism. I went back to Oregon State with a renewed vigor. I started taking more photography classes and really loved it. I remember my father coming to visit me at school ... and me saying, “Dad, I want to be a photojournalist.” He looked at me and said: “Do it well.” I remember that vividly.

|